It has been a busy year for the Landscapes of Protest team. Since the project started in March, we have visited archives in Inveraray, Inverness, Edinburgh, and London and, by the end of year one, will have spent over three months immersed in the eighteenth-century archive.

What we have found has confirmed and, in many ways, exceeded, our initial expectations. Protest was located in local courts, where tenants challenged the privatisation of natural resources, even in the Court of Session, where ‘writers’ (lawyers) were employed to defend residents from eviction. On the ground, tenants resorted to trespass, enclosure breaking, and land invasion, (re)claiming space they believed was theirs. These claims of moral and sometimes, ancestral, ownership found further expression in the multiplicity of ways the tenurial class turned the increasingly commercialised landed estate against itself, for instance by threatening to emigrate to North America to obtain better leases. The array of protest practices, both overt and covert, individual and collective, has revealed an estate landscape enmeshed in deep negotiation between those who owned land and those who worked it and shaped by contestation from members of the rural orders across the social ladder.

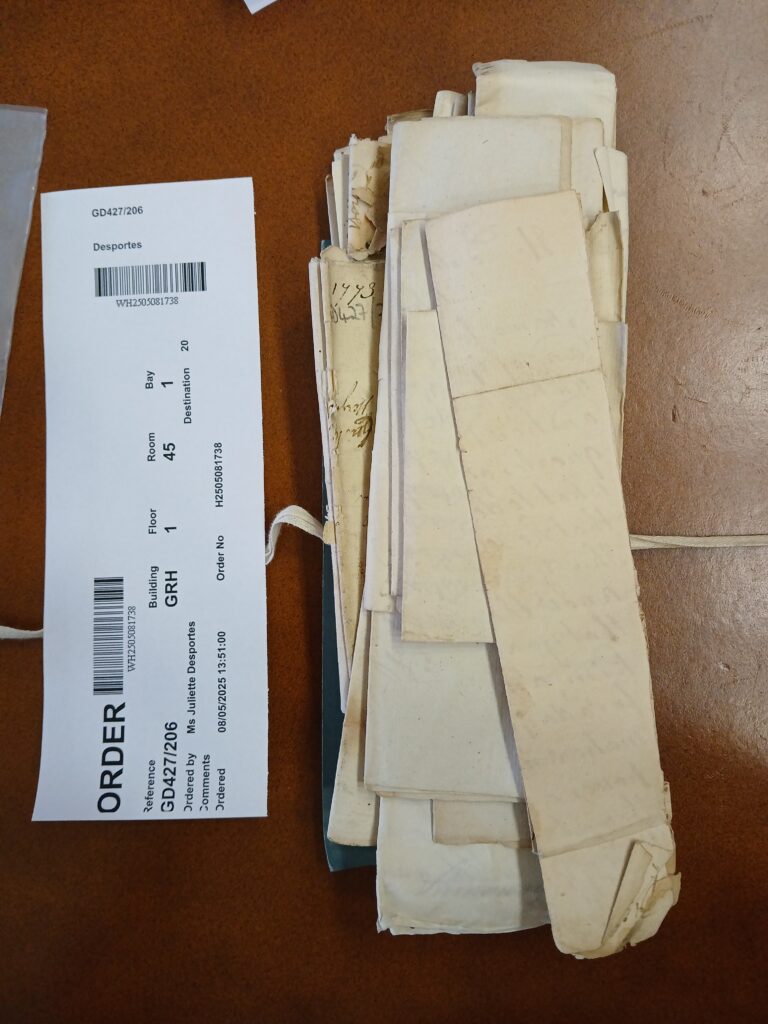

So far, the team has largely focused on three of five case studies: Argyll, the Isle of Lewis, and Strathspey. We were able to consult large portions of the Inveraray, Stornoway, and Elgin Sheriff Courts papers, focusing on civil and criminal processes and, where available, additional barony court and justice of the peace records. Often kept in large (messy) boxes blackening our fingers due to paper dust, legal records proved invaluable to our understanding of the patterns of prosecution and the range of legal strategies employed by the accused to avoid punishment or, perhaps more unexpectedly, thwart estate management.

Some Lewis estate papers. Courtesy of the NRS.

Better known and much more used by historians, estate papers of the Seaforth, Argyll, Grant, and Gillanders families are incredible assets to further capture the complexity of eighteenth-century estate landscapes. Faced with such an array and wealth of material, identifying archival priorities and systematic sample strategies has offered the biggest challenge thus far. Indeed, the quality and sheer quantity of surviving material has at times proved overwhelming but nothing that a sobering coffee break and a sharpening of our pencils could not overcome.

In legal and estate papers alike, common patterns have emerged, such as the importance of the 1770s, a key period plagued by poor harvests resulting in food insecurity and famine. In these precarious times, and as masterfully argued in Marianne MacLean in her People of Glengarry, Highlanders and Islanders often emigrated as a form of protest against the reorganisation of landed estates along ‘improved’ lines. Less attention has been paid to those who stayed, but evidence uncovered thus far suggests that they often relied on their unprecedented bargaining power to demand rent reductions and better tacks, rattling estate management in the process. Correspondence between Seaforth and his factor and legal agent, for instance, fully capture this time of insecurity for the estate, with management often ‘at loss’ at how to recoup lost rents and arrears. In Kintyre, the Duke of Argyll’s demand for cash led to large rent increases and the introduction of English settlers, but this too was met with protest, with some tenants entering ‘combinations’ to prevent the best farms from falling into settlers’ hands.

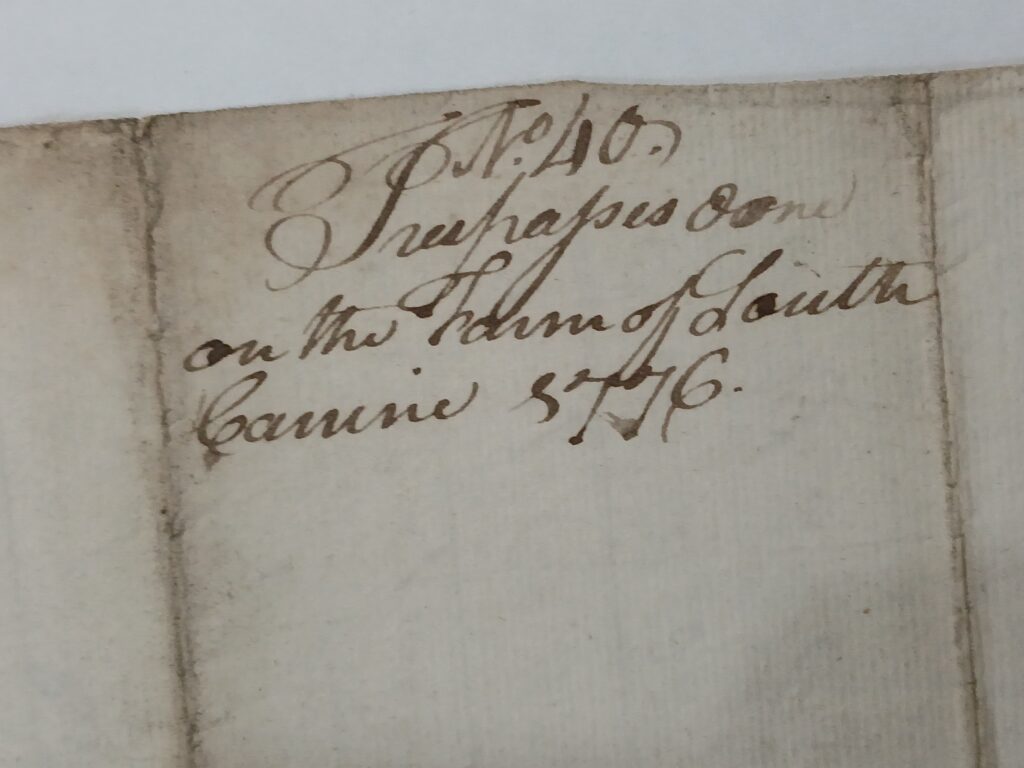

Trespasses reported in Argyll, 1776. Courtesy of the Duke of Argyll.

Another common pattern identified was the consistent opposition to privatisation and enclosure. In addition to the prevalence of ‘social crimes’ such as wood theft and trespass on recently privatised grazings, residents on landed estates broke dykes, fences, and other forms of enclosures and occupied grounds well before the much better-known land raids of the 19th and 20th centuries. Dozens of cases were identified across the Highlands and Islands, such as in 1769 in Ardkinglas, Argyll, where a tenant named Walter MacFarlane ‘in a most wanton and lawless manner broke down and stole away the gate and cabbers of the mark dyke’ which blocked access to his cattle. In the Isle of Sanda, just three km shy from the southern Kintyre coastline, a group of tenants went a step further in 1790, taking ‘violent possession’ of the island to assert their right of pasturage. While the tacksman called these rights ‘mere affectation’, Sanda residents refused to back down, leading to a prolonged legal proceeding in the sheriff court. While the story of resistance to enclosure is virtually untold in the Scottish context beyond the brave challenge posed by the Galloway Levellers in the 1720s, these examples have largely confirmed our suspicion that Scottish (and Highland) experiences of and reactions to privatisation were perhaps not so different than those of its southern neighbour.

If providing but a flavour of the range of material identified, these archival glimpses hint at the amount of exciting work ahead. So, what is next? The team will spend much of the month of February in the National Records and National Library of Scotland, continuing research on Strathspey, legal material, and beginning work on the remaining two cases studies, Caithness and Perthshire. In addition, two articles have already been submitted to academic journals, offering some reflections on Highland protest. Building on papers given alongside Iain at the Scottish Local History Forum and at the University of Edinburgh in October 2025, Juliette will be traveling to Paris in early March to give two papers at the Sorbonne and then sharing some insights about archival research with the Scottish Association of Country House Archivists (SACHA) in Clackamannan. On 30 April, Iain and Juliette will be introduction the project further at the Institute of Northern Studies’ seminar series which should be recorded and made available online.

Another exciting year awaits – all made possible by the support of our funder the Leverhulme Trust and our Advisory Board. We will keep sharing new blog posts on our website about once a month alongside further project updates and news, so stay tuned!

Iain, Juliette, and Carl in Ullapool in April 2025

Leave a Reply