Charlie Hoskins is a Masters by Research student at the University of Edinburgh. He is currently researching agricultural ‘improvement’ in Caithness between 1790 and 1820, focusing particularly on the circulation, implementation, and impacts of new agricultural ideas in the region.

By the final decades of the 18th century, the ‘spirit of improvement’ had reached Caithness. Many landowners and their factors were eager to modernise their farms, as well as the entire region, turning their attention to crop rotations, livestock, enclosures, roads and bridges, and fisheries. These landowners believed that the changes they were making to their estates were necessary for the future financial prosperity of Caithness, a thought that was in line with the ever-growing mass of agricultural literature.

One such Caithnessian landowner was Sir Robert Anstruther of Balcaskie. A native of Fife, Anstruther bought the estate of Bridge-end, in the middle of Caithness, in 1788 and the estate of Braemore, in the south of Caithness, in 1793. With a firm belief in the necessity of ‘improvement’ in Caithness, he swiftly began to undertake an extensive program to modernise his farms in line with new trends, enlisting the help of local farmer and landowner, Benjamin Williamson, Esq., of Banniskirk. Anstruther converted rents that were partly in kind to fully cash, introduced turnips and peas into six-year crop rotations – in contrast to the norm of simply rotating crops of oats and bear –, imported southern ploughs for his tenants, encouraged the building of ditches, drains, and dykes, consolidated farms, converted ‘wastelands’ into arable fields, and sought to expand the road network in the county. He also began to remove tenants who were unable to meet his demands, acknowledging to Williamson that although he was “not very fond of depopulating”, the people were “entire strangers to [him].”

While Williamson, who was now Anstruther’s factor and estate manager, was stationed as a British Officer in Ireland in 1797, Anstruther updated him on the immense ‘improvements’ already taking place: “I can assure you the change of this country for the better is prodigious since you saw it. Agriculture much improved, tennants [sic] houses habitable, rents rising especially for Grass Farms, and land selling as well as in any other parts of the Kingdom.” In Anstruther’s eyes, Caithness was now thriving, and it was all thanks to ‘improvement.’

Elsewhere in the region, other landowners, tacksman and factors were also pursuing a wide array of similar transformations. Most famously, Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster introduced Cheviot sheep onto his farm at Langwell, on the border with Sutherland, in the 1790s. Benjamin Williamson, on his own estate, also farmed Cheviots and worked closely with Sir John to bring Argyllshire cattle into Caithness to ‘improve’ the native breed. Robert Sinclair of Scotscalder, tacksman of Rumsdale and Dounreay, cultivated a large flock of Blackfaced sheep and engaged in trade with the Lowlands. Many farms updated their crop rotations to include green crops, shifting from infield/outfield and runrig field systems to enclosed farms with straightened rigs. Sir Benjamin Dunbar of Hempriggs, himself investing in ‘improvements’ on his estates, feued land near the town of Wick to the British Fisheries Society to develop a commercial fishing industry, with a harbour and new houses. ‘Improvement’ was certainly gripping the minds of the elite in Caithness.

Yet, Anstruther was also aware that many would not readily accept plans for the ‘improvement’ of Caithness. In 1801, in a letter to Williamson about the building of new roads, Anstruther declared that “if you expect to prevent the people from complaining you may well expect to bridle the wind.” Though relatively new to Caithness, Anstruther was right to warn Williamson about the possibility of resistance from tenants.

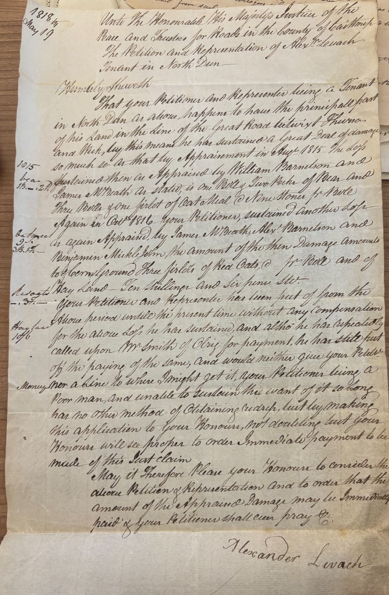

Indeed, tenants did protest against ‘improvement’ in Caithness. The construction of the road between Wick and Thurso (now the A882) through Benjamin Williamson’s estate damaged the farm let by Alexander Levach. In 1818, Levach petitioned the Justice of the Peace and the Road Trustees of Caithness, demanding compensation. An appraisement in August 1815 found that Levach had lost one boll and two pecks of bear, as well as three bolls and one peck of oatmeal. Another appraisal in October 1816 found that the road construction damaged more of Levach’s corn lands, amounting to three firlots of red oats worth ten shillings and six pence Sterling. Being a “poor man” who had not received any compensation for this loss, Levach had “no other method of obtaining redress, but by making this application to your Honours” to recoup his losses.

Alexander Levach’s Petition to the Justice of the Peace and Trustees for Roads in the County of Caithness, May 19 1818, Acc.9872/16, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh.

Much like Levach, the tenants of Robert Sinclair of Scotscalder, the tacksman and factor for Sir John Gordon Sinclair of Murkle, also engaged in litigation to protest the changes taking place on their farms. Donald Hamilton, a tenant in Skaill, refused to remove from his farm in the 1810s. He alleged that he was being removed so that the farms of Borrowston, Skaill and Dounreay in the northwest coast of Caithness could be divided differently. He also cited that one of the farm managers had been “exacting Services”, which Hamilton viewed as unfair and unlawful. As Scotscalder had a growing flock of over a thousand Blackfaced sheep in Borrowston by 1815, a breed which had only been introduced to Caithness in the 1780s, Hamilton’s removal was likely ordered to make room for these ‘improved’ sheep.

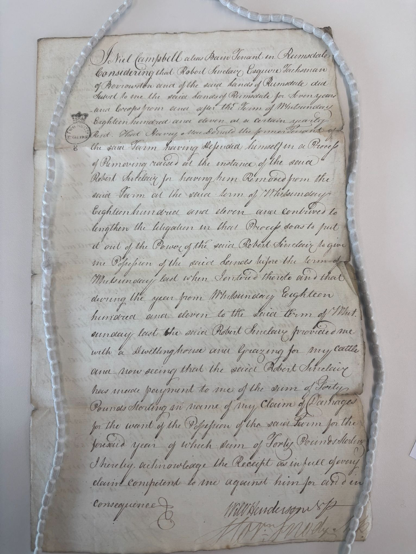

In Rumsdale, within the mountainous part of Caithness, Harvey MacDonald resisted his removal at the hands of Robert Sinclair of Scotscalder, who was also a tacksman on the estate of Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster in this area. In a ‘Discharge and Renunciation’ from Niel Campbell, the tenant who was supposed to have entry onto MacDonald’s farm, to Robert Sinclair in 1812, Campbell wrote that MacDonald sought “to lengthen the litigation in that Process [of removal] so as to put it out of the Power of the said Robert Sinclair to give [him] Possession of the said lands before the term of Whitsunday last.” The archival material does not make clear the reasons for MacDonald’s removal, but it is worth noting that this farm was located in what was deemed the best part of Caithness to introduce commercial sheep farms. Thus, much like Hamilton’s removal, it is likely that MacDonald was resisting the encroachment of ‘improved’ commercial sheep farming that necessitated the depopulation of some parts of Caithness.

Discharge and Renunciation from Niel Campbell to Robert Sinclair, Esquire, 1812, P23/3/3/16, Nucleus Archive, Wick

Alexander Levach, Donald Hamilton and Harvey MacDonald show that ‘improvement’ was not something that was readily accepted in Caithness. Though each tenant came from a different part of the county, they represent a push back against agricultural change that is often overlooked by historians who cover Caithness solely when discussing the work of Sir John Sinclair of Ulbster.

Leave a Reply