Christopher Whatley is Emeritus Professor of Scottish History at the University of Dundee (c.a.whatley@dundee.ac.uk). Part of his published work has been on popular protest in Scotland. His most recent research project culminated in the publication of Harvie’s Dyke: The People, Their Liberty and the Clyde (John Donald, 2025), a study of one of the first rights of way campaigns in Scotland. He has recently become a member of the board of UHI Perth.

Given the attention that has been paid to them, it might reasonably be concluded that there is little need for further research on the subject of Scotland’s food riots. In his seminal work on popular protest in Scotland Kenneth Logue plotted, described, categorised and accounted for those that occurred between 1780 and 1815. Historians have subsequently investigated food riots that occurred both prior to 1780 and after 1815 and demonstrated their ubiquity – the last being those that ran down the east coast in 1847. Local studies have enriched our understanding of the features and causes of a type of popular protest that was endemic in early modern England and Europe. Such investigations have assisted in accounting for regional and even local concentrations of food rioting – factors that were location specific. Even so, underlying most disturbances over food – mainly the Scottish staples, overwhelmingly oats and meal – was a shortage or feared shortage of such basic foodstuffs on the part of low-wage-earning town dwellers who depended for their subsistence on what they could purchase in local markets. Rioting occurred when farmers and merchants prioritised more lucrative markets that were invariably many road or sea miles distant from those towns and villages located in or near the districts where the commodities in question were grown and harvested.

As the primary cause of food related disorder was periodic failure of the market system, there would seem to be little direct or even indirect connection between ‘improvement’ in the countryside and food riots. Received wisdom on the sizeable movement of population to the towns in mid- and late-eighteenth century Scotland is that this was a benign process. The transition from an overwhelmingly rural society to an urbanised one it is argued was relatively smooth – so much so that there was little in the way of popular protest.

Yet carrying out research for a chapter on the Tayside meal riots for a volume commemorating the life and work of the late Enid Gauldie, I was confronted with the possibility that there may well be a link between what was going on in the rural hinterland of Dundee, and an outbreak of what at first sight seemed like a typical bout of food rioting in a port town – very often the locus of such activity.

In the winter of 1772-73, as was usual when there were concerns about the local food supply, meal stores were plundered, and ships in the harbour laden with grain for shipment outwards were attacked. Nor was there anything different about marches by hundreds of town dwellers out to parishes on the outskirts of the burgh, namely Fintry and Longforgan; it was not unknown for urban mobs to scour the countryside in search of granaries and farms where it was suspected that grain and meal were being hoarded. This happened elsewhere in Tayside at this time, during what was a widespread bout of food rioting.

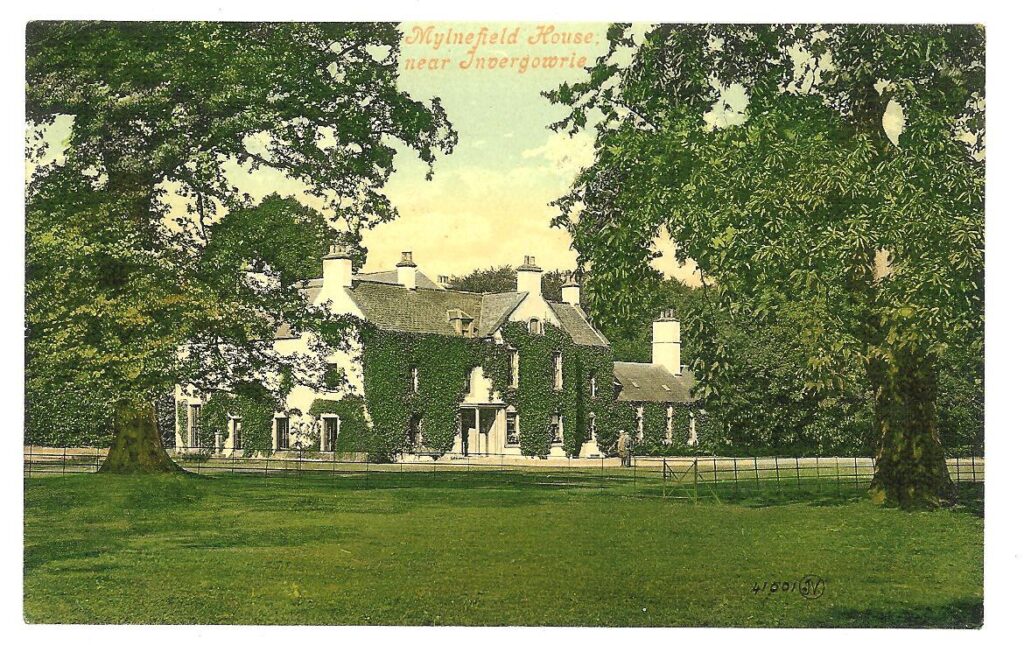

But there was one important difference. In the last-named parish, Longforgan, some three miles from Dundee, lay Mylnefield, the handsome house of Thomas Mylne JP, a socially ambitious, commercially minded and energetic estate improver. Outside the house, servants who thought to protect the property (Mylne and his family were not at home), and denounced as ‘Enemys’, prudently retreated after locking the doors. Consequently, members of the crowd smashed the forty or so sash windows, broke in through the bolted doors and within a couple of hours had comprehensively ransacked the premises. Furniture was broken as were other items. Books, private papers, an eight-day clock, looking glasses, fashionable Delft pottery, silver cutlery, pewter utensils and lace cloth were all taken away, as did ‘a goe carte for children’. Striking is the presence of so many items of a personal nature.

The extent of the damage done to Mylnefield House was unusual – by and large food rioters as with other popular protesters in the eighteenth century showed great restraint as regards private property. Additionally, as was remarked at the time, Thomas Mylne was not a grain exporter; rather, much of his produce was sold to bakers and others in Dundee. Strangely too Invergowrie mill which lay en route to Mylnefield was not attacked, nor was the miller, inn keeper and farm tenant John Bisset. In fact the writer of a lengthy Scots Magazine article on the Tayside riots in their entirety claimed that in Dundee the meal markets were well supplied.

Just why Mylnefield and its servants were the subject of such a serious – and pointed – assault is not immediately obvious. It is true that the price of oats had risen sharply and the collapse of the Ayr Bank in June 1772 had hit Dundee and Tayside hard, with wage cuts and heavy unemployment amongst the town’s recently expanded linen weaving population being the most obvious symptoms of distress. Only the most skilled handloom weavers were able to obtain work, but even they struggled to maintain their families when they were in regular employment. However, what seems to have compounded the difficulties faced by the labouring classes in Dundee and made the town more prone to food rioting was a marked influx of dispossessed rural dwellers – migrants. In recent years there had been “an incredible increasing multitude of poor Inhabitants”, reported David Small, convenor of the burgh’s Nine Trades, who approached the kirk session for their help in January 1773. “From the new modes of Improvement of Agriculture in the Country”, he explained, people had been cleared from their cottages and, having nowhere to live, had been “obliged to take Shelter in Towns”.

The argument that rural dwellers were drawn to the towns by higher wages, rather than being pushed off the land does not apply in Dundee’s case at this time. Without a trade, the uprooted migrants from east Perthshire and Angus had little choice once in the burgh but to engage in unskilled work such as the weaving of plain, coarse cloth. Work of this kind, however, was poorly paid, often below subsistence level. Following the downturn in trade from 1772 was a reduction in employment opportunities for women and children, with devastating consequences for household budgets to which their earnings, albeit meagre and often irregular, had formerly contributed – a “very calamitous” situation.

It is highly likely therefore that one of the reasons the Dundee rioters singled out John Puller in Fintry is that he was one of the landlords responsible for “ejecting the subtenants”. Similar circumstances almost certainly account for the wanton damage done to Mylnefield House.

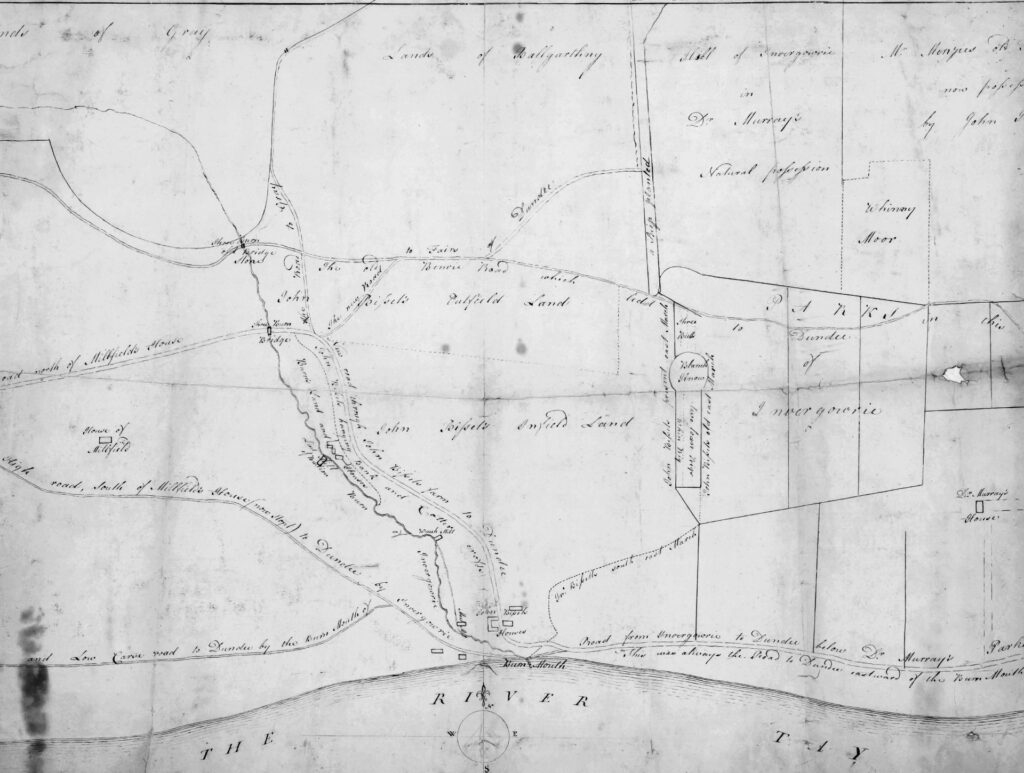

Moorland in Longforgan, formerly used by sub-tenants and cottars in the fermtouns to graze their few animals, had been fenced off while cattle and even sheep – the first in the Carse of Gowrie (the low-lying stretch of land between Dundee and Perth) – were introduced. Thomas Mylne and his gentleman friends had in 1760 driven a new road through John Bisset’s farm, while Mylne himself had stopped Bisset and others from planting whins for kindling their fires. Elsewhere not only had many cottages been removed but so too had “one large village”. Prior to this, estates such as Ballo had been thickly populated with cottars; there had even been a cottar-toun of Invergowrie. Elsewhere in Lowland Scotland it was precisely in small and fast-expanding towns (like Dundee) and villages that former country dwellers clustered, to form an unstable and, for the authorities, a threatening portion of the population.

In both Fintry and Longforgan the ire of the populace was directed towards identifiable individuals and their property and possessions. The assault on Mylnefield was almost certainly inspired by smouldering resentment about the rapid amassing of wealth by landed proprietors like Thomas Mylne who were profiteering at the expense of country people who had lost their homes and, as town dwelling wage earners, were struggling to feed their households. Notably, it was weavers and those mainly in lowly occupations who were the most numerous members of the rampaging crowds. Fuelling their sense of injustice was the social distance that opened up as a result of Mylne’s adoption of a more opulent lifestyle. The family had transitioned from tenant farmers to status-conscious lairds who listed amongst their possessions lost during the riot, “Two best feather beds, London made”; these were twice the price of the Scots made versions.

Those driven from lands on which they and their ancestors had long lived sought retribution. What happened at Fintry and Mylnefield was the outpouring of anger against enforced change in the Angus and Perthshire countryside. This was far from “evolutionary”, or benign, as has been claimed for Lowland Scotland generally. Rather, for those on the receiving end, agricultural reform was highly disruptive, and deeply distressing.

The situation in and around Dundee may not have been typical. It may have been limited to a specific period of time. Even so, what this example demonstrates is the importance of local, in-depth investigations that get behind the boldly proclaimed sweeping generalisations.

Further Reading

Kenneth Logue, Popular Disturbances in Scotland, 1780-1815, Edinburgh, John Donald, 1979.

Christopher A. Whatley, ‘Millers, meal mobs and migrants: re-investigating and re-evaluating the Dundee food riots of 1772-73’, in A Beacon of Curiosity: Essays on Social and Industrial History in Honour of Enid Gauldie, Abertay Historical Society, 2025, forthcoming.

Christopher A. Whatley, ‘Roots of 1790s Radicalism: Reviewing the Economic and Social Background’, in Bob Harris (ed.), Scotland in the Age of the French Revolution, Edinburgh, John Donald, 2005, pp.23-48.

Leave a Reply